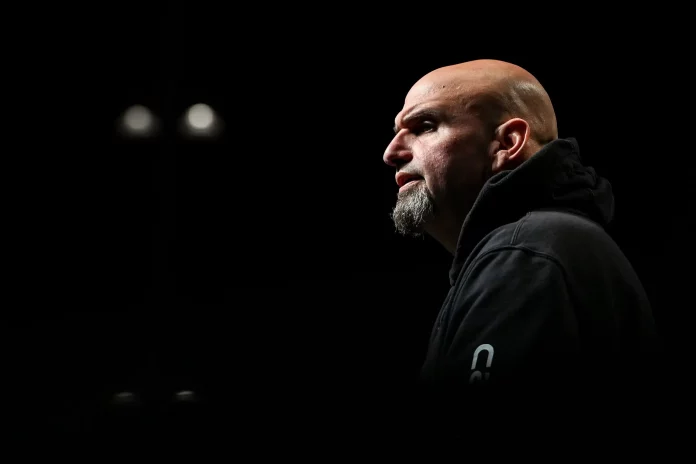

Pennsylvania’s newly elected Sen. John Fetterman has been receiving inpatient treatment for clinical depression since checking into Walter Reed National Military Medical Center earlier this month.

The 53-year-old has been voluntarily hospitalized since Feb. 15 at the recommendation of Congress’s attending physician, Brian P. Moanhan.

This is not Fetterman’s first publicized hospital visit, the first being after he suffered a near-fatal stroke in May, according to NPR, days before primaries for the 2022 midterms.

After his stroke, it was revealed that Fetterman had been previously diagnosed with cardiomyopathy, which decreases the amount of blood the heart can pump, and was not taking his recommended medication.

Fetterman returned to the campaign trail less than two months after his stroke but continued to experience auditory processing issues.

About one in five stroke survivors suffer auditory processing issues, according to the National Library of Medicine.

“It would be no different than somebody that is deaf using closed captions or reading lips,” Linda Yelen, a stroke coordinator at one of UPMC’s hospitals, said.

Yelen oversees one of the stroke programs through all of UPMC and works as a sub nurse at SRU. She started nursing in 1986, working in the ICU until switching to the E.R. where she worked until five years ago.

Fetterman would move on to defeat GOP opponent Mehmet Oz by nearly 5% to claim Pennsylvania’s open Senate seat.

While NPR reports that Fetterman has experienced depression throughout his life, about 30% of people who survive life-threatening events that require intensive care will develop symptoms of depression.

Strokes change how the brain functions and can affect a person’s ability to experience positive emotion according to Kristina Benkeser, SRU’s director of health services and student health and wellness. The changes in the brain can erode the natural counterbalance to depression and can also cause personality changes.

As a health care professional working with mostly young people, Benkeser said mental health illnesses are one of the main things she treats.

Depression is not uncommon; in Pennsylvania alone, nearly 40% of adults have reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

In stroke survivors, nearly one third suffer post-stroke depression. Their chance of experiencing depression symptoms start to decrease after one year, then slowly decreases for up to five years afterward.

Factoring in stroke survivors with a history of mental illness, around 50-55% of stroke survivors eventually suffer symptoms of mental illness, Yelen said.

A senior aide who spoke to The Washington Post on the condition of anonymity said in the weeks leading up to his hospitalization, Fetterman appeared increasingly withdrawn, not himself, malnourished and dehydrated.

Marie Finelli, 30, suffered a stroke on July 19, 2017, when she was 24 and did not receive lytic medication to break up the clot as quickly as Fetterman.

Her stroke paralyzed her left vocal cord leaving her with trouble speaking, walking, balancing and swallowing among other symptoms.

Finelli recalled her own struggle with depression before and after stroke. Before her stroke, she was on “five milligrams or something” of antidepressants, what she described to be a very, very minimal amount.

After her stroke, she needed a psychiatrist because her family doctor was not authorized to prescribe the new dosage she needed. She also now had to account for blood thinners, cholesterol or other medications she’s taking that could interact with her antidepressants.

“It was like night and day after the stroke,” she said.

A week before his voluntary hospitalization for clinical depression, Fetterman was discharged from The George Washington University Hospital where he spent the night for observation after feeling lightheaded, according to spokesman Joe Calvello.

A senior aide for Fetterman said it is possible he could be hospitalized for weeks but neither his staff nor the governor’s office expect him to resign from the senate.

Since Fetterman’s hospitalization, many colleagues and strangers have reached out to express their support for the senator. Of the 1.8 million adults in the state that cited mental health conditions, nearly 600,000 of them did not receive any treatment in the last year.

Benkeser realizes that putting his depression in the public eye “comes with the territory,” but still feels appreciative of him for being open with that is “really a deep, personal matter.”

“When we see celebrities,” she said, “whether they’re movie stars, music stars or TikTok stars, or others that say ‘there’s times in my life when I need help and I’m going to get help,’ I think it gives the message that it’s okay for me to get help, and I am not alone.”

Gisele Fetterman, the senator’s wife, tweeted a response she received from a supporter who was encouraged by Fetterman seeking help to go to therapy for the first time since he was diagnosed with depression more than a decade ago.

People with depression often think that others may see them as less capable. Workplace pressures can also bring out some situational depression and make underlying depression worse.

“I think he’s not only a positive example to the people of Pennsylvania,” Benkeser said, “I think he’s a very positive example to his fellow congressmen and women.”

Aides to Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro said they are not taking any steps to prepare for the possibility of Fetterman resigning. In an interview with The Philadelphia Inquirer, Shapiro voiced his support of the senator, saying he was inspired by Fetterman’s courage in making the decision to get help.

Benkeser, Finelli and Yelen all agreed that strokes have a spectrum of severity, and they were optimistic that Fetterman’s ability to serve was not compromised.

“There are some people who don’t even know that they’ve had a stroke because they’ve been very, very small,” Yelen said. “There are other people who have had a stroke and ended up in a nursing home for the rest of their life because they’re so involved.”

In the hospital, Finelli recalled meeting another stroke survivor that could not repeat a word back to a nurse.

“It made me realize that there are different kinds of strokes,” she said. “Some people are way different afterward, and other people are fine.”

Generally, stroke survivors sometimes face difficulties with what medical professionals call “activities of daily living.”

This could look like trouble moving limbs, difficulty eating or speech difficulty which can include trouble physically speaking, listening, processing or finding the right words. Finelli expressed some of these difficulties.

However, some patients endure massive strokes and go on to live completely fulfilling lives working full-time or multiple jobs, Yelen said.

The recovery time from a stroke depends on severity, location, age and how quickly one seeks treatment. Quickly getting the necessary lytic medication also decreases the level of disability a stroke survivor may face.

Necessary accommodations also depend on what part of the brain is affected.

Finelli also appreciates Fetterman for providing representation in Congress for stroke survivors and people suffering from mental health illnesses. She is passionate about spreading awareness for stroke symptoms and getting help quickly.

Benkeser is also optimistic the challenges from Fetterman’s stroke could allow him to better represent people with disabilities and life-altering illnesses, and she advises some “watchful waiting.”

“If he doesn’t think he can do the job, I hope he would step down,” Finelli said, “but I’m confident he can get the job done. He might just have to do it a different way.”

“Mental health is being accepted by our country,” Yelen said, “and I really hope people look at this and realize it could be them or their loved one.”