Disclaimer: the following story contains mentions of mental illness and may be triggering to some readers. Please read with caution at your own discretion.

To submit a care report for yourself or someone you are concerned about, click here.

If you or someone you know needs help, local help is available through campus police (724-738-3333), the Health Center (724-738-2052) the Counseling Center (724-738-2034) and student support (724-738-2121). The National Eating Disorder Association helpline is available Monday through Thursday from 9 am to 9 pm and Friday from 9 am to 5 pm (800-931-2237).

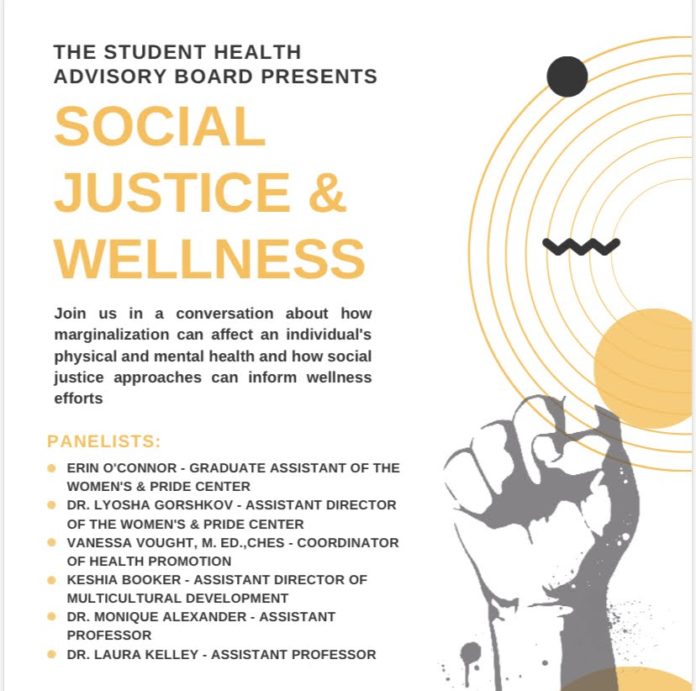

The Student Advisory Health Board (SHAB) hosted its first meeting of the semester Tuesday in the Smith Student Center Theater to discuss social justice issues and how they can affect the health and well-being of certain individuals.

Panelists included Vanessa Vought, coordinator of health promotion and co-chair of the President’s Commission on Gender Identity & Expression and Sexual Orientation (GIESO); Erin O’Connor, graduate assistant for the Women’s and Pride Centers; Dr. Lyosha Gorshkov, assistant director of the Women’s and Pride Centers; Keshia Booker, assistant director of multicultural development at the Office for Inclusive Excellence (OIE); and Dr. Monique Alexander and Dr. Laura Kelley, assistant professors of the Elementary Education and Early Childhood Education program.

Gorshkov began the discussion by personally defining what social justice means to them.

“For me personally, social justice is action and reaction,” Gorshkov said. “You can’t sit at a table with public officials and talk about issues and then not take action.”

They explained that the Women’s and Pride Centers, in terms of social justice, have been trying to empower specific groups they serve to advocate for themselves rather than rely on institutions and politicians.

O’Connor continued the conversation, saying she has been focusing on one specific social justice concept: equitable access to rights and resources. She added that it’s important to distinguish the differences between “equality” and “equity,” explaining that equity gives people or groups what they specifically need to be on the same level as other groups.

“If someone is already 50 feet ahead in a race, do they really need something more to win?” O’Connor said. “Or do we need to look back at the people who are behind and figure out what is causing them to be so far behind?”

Alexander added onto the point O’Connor made, saying systems of oppression under-ride the inequities that come to people of different classes or races keep people from having access to what they need.

“We as a society, as small groups of people or as large organizations, are essentially fighting to get justice for people who haven’t traditionally had access to services or practices that they need,” Alexander said.

Karmyn Ramirez, chairperson of SHAB, posed the question, “What does social justice look like on SRU’s campus?” The question was opened to the panelists and members of the audience as they’ve experienced and witnessed social justice issues at SRU firsthand.

O’Connor discussed the formation of the Social Justice Committee (SJC) within the Student Government Association. She said the implementation of the SJC is a wonderful example of social justice at SRU. She commended other campus organizations — the Feminist Majority Leadership Alliance and the Black Action Society — that use their identities, voices and power to bring to light issues that need to be focused on.

An audience member asked panelists what each office — the Office for Inclusive Excellence and the Women’s and Pride Centers — do specifically for students, and Booker took the opportunity to explain in-depth what the OIE is and does.

“[The Office for Inclusive Excellence] operates for holistic development, so it depends on what exactly you’re looking for,” Booker said. “If you come to us for academic reasons, we can take care of that. If you come to us for something involving any marginalized identity, we can assist you through whatever challenges you’re facing. ”

She continued to explain that they host campus-wide diversity programming. She added that, given that SRU is a predominantly white institution, the OIE’s various programs allow students the opportunity to experience other identities and cultures.

Another student raised the concern that social justice seems to be optional on SRU’s campus because it’s not reinforced through academics and that students can choose to not educate themselves.

Alexander responded, saying her observations are correct. She said there are curricular supports like Global Engagement courses to ensure that students receive a more well-rounded education, but if the curricula of individual classes don’t include a component of equity and social justice, then students obviously have the choice to avoid those topics.

Booker added to the discussion, saying another problem on SRU’s campus is that the community seems to have tunnel vision and hasn’t moved past racism.

“People tend to only see social justice through the identities that we choose to identify with,” she said. “If I can’t see past the color of your skin, then how am I going to deal with any other aspect of your identity? We’re not as progressive as we would like to claim to be, and that’s not because of a lack of opportunities. We’re not holding each other to a standard that promotes social justice.”

Ramirez then asked the panelists how the marginalization affects health and how social justice intersects with health and wellness.

Kelley, professor of early childhood education, contributed to the conversation, saying people tend to talk around issues such as marginalization and its effects on wellness because of sensibilities or political divisiveness or simply wanting to be polite.

“That’s something we have to get over,” she said. “If we can’t have a real conversation about real issues, then it’s going to be very difficult to make progress.”

She added that, in regards to wellness, she often thinks about the mental health of college students. In reference to a national student health survey, she said students are struggling with their mental health for multiple reasons. In the aforementioned student health survey, she said students of color reported comparable rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation, but their access to needed resources is incomparable.

“This is probably for a myriad of reasons, but one thing I’ve witnessed personally is that a lot of students access health resources via the faculty they feel connected to because we interface with students all day, every day,” Kelley said. “If you don’t feel safe and connected to the people you see every day, it’s difficult to feel safe and connected within the greater community.”

Alexander added to this point, saying she and Kelley completed a study together in the fall that specifically targeted students of color in the College of Education. She said one of the study’s findings was that black students only access a handful of faculties in a time of crisis. In the survey, she said students often used the terms “normal” and “regular,” from which they concluded that students of color are treated very differently and possibly experiencing microaggressions not only from their peers, but from faculty as well.

“When they talked about accessing white faculty, only three were mentioned,” Alexander said. “We need to hire faculty who have more diverse experiences, even though they may be white. In the context of the College of Education, they are going into a profession that is 90% white, and our college reflects that.”

Booker then said students may not have the ability to care about both social justice and wellness. She referred to a piece of paper in front of her as “bandwidth,” saying that if students have to worry about meals, textbooks, identifying with their professors and peers, and dealing with the inherent racism within the community, they probably don’t have much time or space to worry about their health and well-being.

Vought, coordinator of health promotion, said that the public health industry itself has done a lot to contribute to the marginalization of certain groups even though the priority of the health care industry is to help all people in need.

“They’ve often neglected certain populations,” she said. “Something I tend to see even now is that, while we do at least recognize that health care disparities to exist, they don’t do a very good job of really looking at those structural issues.”

O’Connor added that another issue that lies within the intersections of social justice and wellness is lack of representation.

“Why is it that I had to drive 35 minutes to find a counselor who I knew I could be completely open about my sexual orientation with?” O’Connor asked. “Finding that representation and connection is very hard when you’re already a minority within your community.”

Ramirez then asked the panelists, starting with Vought, what social justice approaches that could be applied to wellness efforts in order to ensure that SRU is being inclusive in its health promotion practices.

Vought said being mindful is important in being inclusive — being mindful of what is being taught and who is being marginalized and excluded, she said, will break the cycle that ultimately perpetuates itself.

“We have to try to be as inclusive as possible,” she said. “We won’t always get it right the first time or every time, but we need to be open to learning more, educating ourselves and being receptive of feedback.”

Gorshkov said he believes speaking up for yourself and your beliefs is essential to the intersect of social justice and wellness. He added that, though it may seem scary to some, especially at such a young age, you’re still able to determine what you want to fight for.

“We’re not in a Russian dictatorial state,” he said. “We’re in the United States. You’re free to empower yourself. We’re not all going to be Martin Luther Kings, we’re not all going to be Rosa Parks, and you might have to be annoying and be a pain in the neck sometimes in order to achieve something, but you can still become a leader and educate others.”

Kelley said it’s important to also consider how policies and systems affect people differently. Those who have capital or power in certain situations, she added, it’s important to be receptive to feedback, to not be defensive, and to figure out how to resolve the issue. One specific example she made was something everyone in attendance was aware of: classroom attendance policies.

“It’s not my job to decide if you’re well enough to come to class,” she said. “I can’t say, ‘You need to take care of yourself and do what you need to do for you, but don’t you dare miss more than two of my classes.’ Those two things are in conflict. For people who are juggling lots of different things, we need to think about the reasons people might need to miss classes and figure out how we can work with them to get them what they need efficiently and appropriately without punishing them for having a lot on their plates.”