A student with a disability may rely on accessible design in order to go to class, a dining hall or an on-campus event; however, a person’s ability to navigate campus and enter or exit buildings often lies in the hands of community members. When community members possess this responsibility but lack proper knowledge, they can prevent a person’s ability to navigate campus by parking in accessible parking or even unnecessarily pressing accessible buttons on doors.

Of the 550 students who receive accommodations through the Office of Disability Services (ODS), 120 students have a medical/health issue and 18 students have a physical disability. Although accommodations and laws support these students—who make up 6.23 percent of SRU’s undergraduate and graduate population—factors including equipment malfunctions, geography, signage and weather all impact accessibility, an issue that is often complicated at a university commonly referred to as “Snow and Rain University.”

Supports for persons with disabilities

Accessibility is defined in terms of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 for any public entity that accepts federal tax money. Mostly recently, the Department of Justice revised the Standards for Accessible Design in 2010 to apply to the “design, construction, additions to, and altercations of sites, facilities [and] buildings.”

According to Vaughn Bicehouse, a special education professor, ADA standards provide rights to people with disabilities they didn’t receive until ADA standards took effect in July 1992.

“They were second-class citizens who couldn’t get out of their house or get to work,” Bicehouse said.

The Standards for Accessible Design, however, do not impact existing facilities unless an altercation is already underway, creating a “grandfather effect” that impacts older buildings on campus.

“You only have so much money, so that was a definite component,” Toni Mild, a special education professor and former public school administrator, said. “If you made major structural changes to your facility, ADA came into play. It was no longer grandfathered in.”

Through ODS, students can receive accommodations to help them navigate campus. The most common accommodation is extended test time and students can receive accommodations for priority seating and extra time to get to class.

According to Natalie Burick, director of ODS, the accommodations a student receives are determined on a case-by-case basis, a norm in higher education.

“Most students who need a specific classroom accommodation can work with the faculty on achieving that,” Burick said.

Kim Coffaro, assistant director of ODS, is also the co-chair of the President’s Commission on Disability Issues (PCDI). The 22-member commission features eight student members from various special education or therapy majors and “seeks to create a campus environment and climate that is free of barriers and discrimination and to empower people with disabilities to be full participants in all facets of university life.”

Burick serves as an ex-officio member of PCDI along with Scott Albert, assistant vice president of facilities, planning and environmental safety, and Holly McCoy, assistant vice president of diversity and equal opportunity.

“Any time any issue is brought to us concerning accessibility, Scott’s on the commission and we discuss that with him,” Coffaro said. “He brings

Students investigate accessibility

In fall 2018, 630 students declared a major in recreational therapy, early childhood/special education or special education programming. In these majors’ required classes, students investigate accessibility on campus through hands-on learning experiences.

In Mild and Bicehouse’s 100-level special education courses, students operate a wheelchair in either McKay or a specified spot on campus or in the community. In Bicehouse’s course, students analyze the accessibility a location on campus using the four priorities under ADA and recommend changes to make structures ADA compliant.

In the recreational therapy department, students in Recreational Therapy for Physical Disabilities participated in a 48-hour wheelchair challenge, and students in Inclusive Leisure Services completed an accessibility survey in different areas of campus. Michaela Sykes, a sophomore recreational therapy major and PCDI student member, complied a list of barriers discovered by students in the two courses.

Sykes worked with Heather Bright, a recreational therapy professor who teaches the two courses, to create the list.

“[Bright] thought it would be a good idea for us to jot down a list of things we noticed,” Sykes said. “Our jobs as RTs are going to be to help people rehabilitate and get back into the community. Obviously, not all communities are 100 percent accessible.”

Sykes presented the list at to PCDI and Scott Albert, assistant vice president of facilities, planning and environmental safety and ex-officio PCDI member, provided updates on each presented issue.

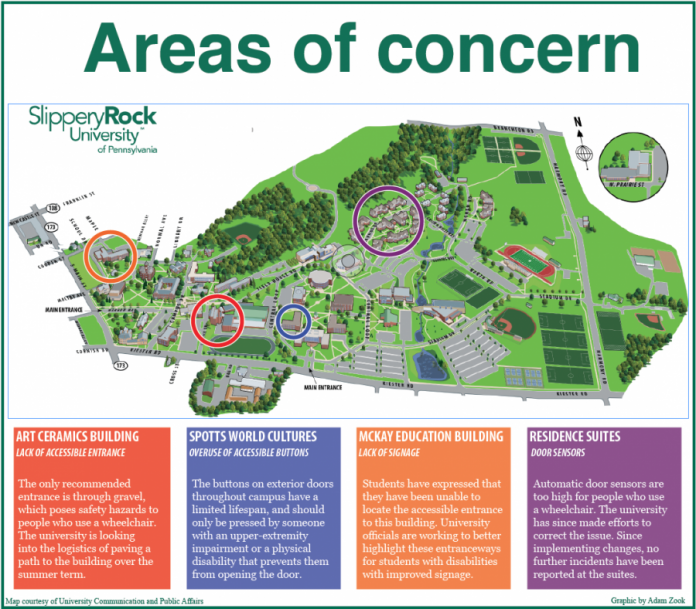

Areas of concern

One campus-wide concern mentioned in the accessibility barriers report is accessibility buttons. Because the buttons have a certain lifespan, the button will eventually fail to work after a certain number of uses.

“A lot of the comments on here that I noticed from the other students and myself was a lot of those buttons not working,” Sykes said.

Sykes also said that some buttons operate via a wireless signal which can be disrupted, a problem maintenance can’t necessarily control.

“They try their best to keep updating those buttons and make sure they all work,” Sykes said.

Two areas of campus were identified as lacking signage for accessibility. In McKay Education Building, two accessible ramps exist on either side of the building, but the entrance is difficult to find. One of the accessible entrances enters into the auditorium, where many larger lecture classes are held.

During the initial survey, students couldn’t locate accessible seating in the Mihalik-Thompson Stadium. Albert reported that the seating is on the home side around the 50-yard line.

“We were talking about better signage and better awareness that this is an option available to them,” Sykes said.

Another concern discovered was the entrance to the Art Ceramics Building. According to Sykes, who had a class in that building this semester, the only recommended entrance into the building is through gravel, posing an accessibility barrier.

“It’s not really accessible for a wheelchair to get over all those rocks,” Sykes said. “That’s not necessarily safe for the student, and not necessarily good for the wheelchair. It can cause a lot of wear and tear.”

After a recent PCDI meeting, Albert announced that his department will be looking into the logistics of paving a path to access the Arts Ceramics Building.

Weather conditions and geography of campus greatly impact accessibility of sidewalks. Cracked sidewalks poses a particular accessibility concern.

Lauren Sims, a PCDI member and student with a vision impairment, described that she sometimes hits cracks in the sidewalk while using her cane.

“I’ve noticed a lot of sidewalks have cracks in them, so that can be a problem with my cane sometimes,” Sims said. She added that the sidewalks near the library and in the quad have a lot of cracks.

Environmental barriers, especially hills, impact how sidewalks and ramps are constructed. If an incline is too steep according to ADA standards, a sidewalk must be paved with a lesser incline.

“They try their best to make pathways that are going to be convenient, but they look into inclines of hills,” Sykes said.

According to Sykes’s report, the ramp near the Student Health Center is unsafe in winter conditions and needs repaved; a work order has been submitted for this ramp.

Students also reported that some door sensors for the residence suites were too high for people in wheelchairs. Upon further investigation, Albert reported that the sensors are in working condition.

After creating the list of accessibility barriers, Sykes was surprised that certain barriers were not problematic under ADA standards. For example, the exterior doors of the Smith Student Center exceed the five-pound limit. According to Sykes, that weight limit only applies to interior doors.

“Hopefully in the future, some more laws can get passed to really push for that accessibility in all buildings, all public spaces and interior and exterior doors,” Sykes said.

Turning education into action

PCDI is now taking the information discovered in the barrier reports to educate others. Beyond reporting accessibility barriers, PCDI created “mindful” tips to educate the SRU community on how to assist people with disabilities. The campaign featured eight tips, including not using accessible bathrooms and parking spaces, by hanging signs around campus.

“Hopefully, through that and social media, we’re able to continue to communicate those messages throughout the year,” Coffaro said.

Another “mindful tip” was for people to not press accessible buttons unless they need to in order to open a door.

“A lot of that has to do with people just not realizing and pushing it when they don’t actually need it and running out that lifespan,” Sykes said.

Coffaro said that anyone who finds an accessibility barrier should report the issue to the information desk at the Smith Student Center.

“Be a voice,” Coffaro said. “If you see an issue, go to the information desk and report it.”

Bicehouse emphasized the importance of reporting accessibility barriers, even if the report does not have a disability themselves.

“Sadly, the ones that typically need it aren’t the ones who complain,” Bicehouse said.