Finding a good parking spot on campus is famously difficult. In a Google survey posted on The Rocket’s Instagram, Facebook and Twitter pages, 97% of students agreed that there should be more space to park. As it turns out, SRU students and administration have been dealing with the same issue for over sixty years.

“You can only get a parking spot if you’re here before 9 a.m.,” said senior Sophia Geitner. “After 9 a.m. … you’ll never find a spot.”

Sixty-six students took the survey. Participants ranged from freshmen to grad students, with about one-third living on-campus and two-thirds living off-campus.

One question asked how they “would describe the process of finding a parking spot.” Responses included “terrible,” “stressful,” “difficult” and “frustrating.” Others were more descriptive.

“Very much like playing parking roulette,” one said. “Sometimes you get a perfect space and sometimes you’re ten minutes late to class.”

One student compared the experience to the Hunger Games; another compared it to Squid Game. A few were more impartial, writing answers such as “depends on time of day, but can be hard depending on location.”

Almost 90% of students believe it’s harder to park on campus this year than it has been in previous years. However, one student’s deep dive shows that SRU’s parking issue is not a new one. Stone Helsel, a senior secondary education major, covered the problem for a research project last fall.

When Slippery Rock University opened in 1889 as Slippery Rock State Normal School, almost every student lived in dormitories on campus. Any visitors could stable their horses across the street. The land was not close to a train station, the main method of transport; the roads were unpaved and meant for walking; there was “only one practical road through the campus,” according to Helsel. In the 1800s, it was practical, but it may have laid the groundwork for future issues.

At first, when cars became widely available, most students were not allowed to use them on campus.

“University deans could issue ‘eligibility certificates’ on a case-by-case basis, usually for students who had to help out on the family farm or had to care for ailing parents,” wrote Helsel.

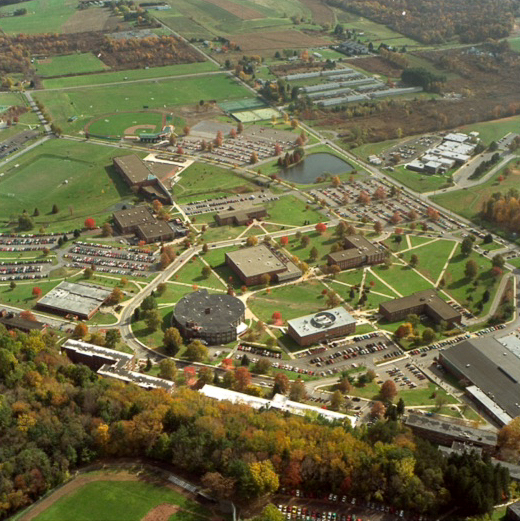

The number of students who could have vehicles expanded until all restrictions were dropped in 1982. Gradually, parking became more regulated, and new lots ate up green space all over campus, including a large outdoor garden. This was a response to the “parking problem” first mentioned by administration in 1958.

When the university opened, 168 students were enrolled. Today, there are over 8,000. Administrators have tried to keep up with the rising population through building projects, but still, there are growing pains.

The final survey question asked students for any other comments about parking.

“The design of the campus makes it hard for students to walk to classes as none of the spots are close to the buildings besides staff parking,” one observed.

Some had ideas about how to fix the problem: “Should be labeled as student parking only. No commuter lots [or] other specific labels. If I am going to be paying extra fees for parking, I should be able to park in any lot besides staff without being ticketed.”

“To take care of on campus parking, I think residents should have designated parking lots depending [on] where you live,” another wrote. “Other colleges do this and it just makes sense.”

Yet another student said that “people complain to [sic] much.”

The same complaints have been repeated in one form or another since 1958. As of now, the solution is still not clear.